If National Geographic had a travel agency, Ruth Daniel would be its best customer.

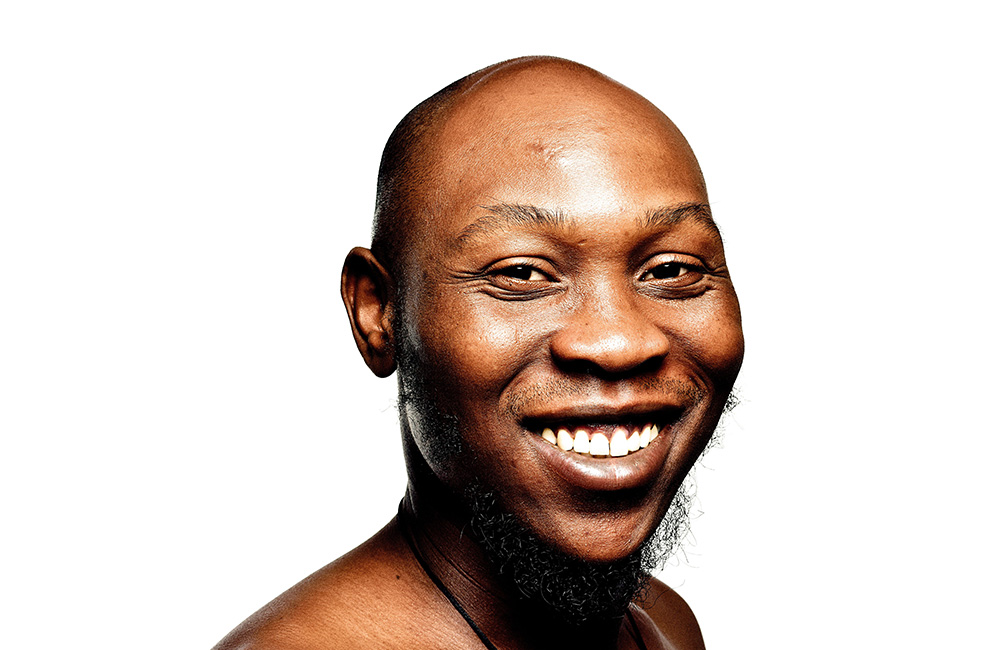

Daniel is the energetic CEO/Artistic Director of In Place of War (IPOW), a Manchester-based organization working with arts, creativity, culture and entrepreneurship in places of conflict around the world; and the founder of Un-Convention which has overseen some 80 events in over 25 countries in 9 years.

IPOW’s primary objective is to guide and empower young change makers in order to enable local communities to create their own creative opportunities in the world’s most challenging environments. This is done through the creation of cultural spaces, supplying unused recording and film equipment, providing alternative education, and taking advantage of the mobility of artists in the world.

IPOW collects equipment to establish new music studios in the world’s most marginalized communities, including Nablus in the West Bank; Soweto in South Africa; and in four locations in Uganda.

IPOW recently secured over $325,000 US in funding from a range of funders to host numerous projects spanning multiple countries, including bringing international artists to the UK. Its GRRRL project, a global series of collaborations by female artists from around the world, launches in Manchester later this month.

IPOW is also using the funding to develop a refugee integration project, working in Lebanon, Sweden, Germany, Greece, and the UK to enhance intercultural dialogue, and to explore best practices among organizations that work around the issues faced by immigrant, and refugee communities in these countries.

Launched by Daniel in 2008, Un-Convention is a global grassroots music event and community entity that meets physically, and virtually to share ideas; discuss and debate issues around music, technology and creativity; and facilitate member’s engagement with their peers.

This award-winning cultural producer, activist, and social entrepreneur was honored April 3rd (2017) at the Artist and Manager Awards in London with a Pioneer award recognizing her role as a trailblazer in the British music industry.

How many countries have you visited on behalf of your work?

I tried to work it out, and it’s not as many as you’d think. I’ve been to some countries many, many times. I’ve been to Uganda 13 to 14 times. I have been to Zimbabwe, and Brazil the same. Being from the UK, I can travel anywhere I want. You think of being Palestinian or about certain people who can’t do that. I am really lucky I was born where I was born.

Still, with your passport showing some of the world’s most troubled spots, you must ring some security bells trying to enter the U.S.

Oh, when I go to the States it is intense security.

What do your parents think of your career?

I don’t know if they quite understand it. I think they sometimes get a bit confused but they like that I do it. In the past, they were quite scared that I was going to the Congo or elsewhere on my own, and they worried. The last time I was in Sousse (Tunisia) I stayed on the beach where the attack happened in 2015. I told my mom, and she was like, “Oh my God, Sousse. Can you bring me back a carpet?” She was not so bothered by what had happened there but, for her, it was an opportunity to get a new carpet. So they don’t really mind anymore.

[The incident in Sousse–an extremist attack on 38 tourists in the summer of 2015–traumatized and stigmatized the inhabitants of Sousse, and made Tunisian tourism plummet. However, two years later things have changed. The locals are out in the streets, and on the beaches again, and tourists have started to return.]

You have visited some very dangerous locations where you have had guns pointed at you.

Yeah, Un-Convention has taken me and the people that we work with to all sorts of places. You can get into some hairy situations, but most of the places that we go to have vibrant, dynamic communities with people just making cool sounds.

C’mon Ruth, when you and your team went to Colombia for the first time you passed through the border into one of the most dangerous neighborhoods in the world, Comuna 13, and you were asked to sign forms about where your bodies would go if you were shot. Your group was told, “Don’t get your cameras out, and make sure you stick together.”

Yeah, yeah, yeah. There’s that. But you go to those places, and it’s kind of surreal. One of the things we did in Colombia was that we had a game of football organized with the hip hop guys in Comuna Trece. There was the paramilitary walking around the sidelines with machine guns, and there were people from the community looking on. Here we were on top of a mountain in Colombia. At the time, I was really young, and I just thought, “Wow, this is something really special.” My understanding of all of the places that I’ve been to has never been from a tourist perspective. It’s been from a community perspective. What you find is that these places are always perceived as one thing, but you go to them, and you see something else. I see so much beauty and dynamism in those places. I really don’t want to sensationalize it (the violence). Yes, there have been some difficult moments, like being in the middle of the Congo with a guy with a machete, and I’ve been held at gunpoint. But it’s always been okay. I’m here.

Out in the field have you ever been the receiver of unwanted attention in what could become a dangerous situation?

Well, I was in a southern African country, and the deputy general commissioner was at the hotel bar, and he offered me a drink. I didn’t know who he was. It was after hours, and I couldn’t get a drink, so I said yes. Just before this, I’d been chatting to some South African white guys about race, and I was being quite feisty. The deputy general commissioner came over, and he said, “You are here making a very strong presence analyzing everything that is happening.” I said, “Nice to meet you too.” I was then told who he was. He went on to interrogate me about my work, about England, about my views on race, and other things. He thought I’d planted spies in the nearby garden. I was really honest about what I do, and the changes that I want to see in the world. Everyone around the table was constantly trying to get me to stop talking, or to be less honest. I felt like I had nothing to hide. He said that I was a vixen and that I was a strong woman to take him on. I was being kind of proud of myself when he then tried to pull me, inviting me back for a bottle of wine.

What staff Is in place for In Place of War?

Well, we are not based in the University of Manchester anymore We are still partners with the university, and do certain parts of research there. We are still based in Manchester, but we are independent as of this year. We have broken out from the university for various reasons, including that we can now have more independence. Also, the university is so big which made it quite difficult to work. We have an all-female staff of four, and we have an amazing board of academics and change-makers.

With Brexit signifying the UK’s intended withdrawal from the European Union has there been greater problems attaining work permits for musicians from other countries to work in the UK?

We have always had problems getting people into the UK. We have been dealing with projects for 30 years. As a general rule, 50% of the people we invite don’t get visas. It’s usually 30% to 50% of one group. The last time, a woman arrived from Zimbabwe, and she didn’t get her visa. We then reapplied. We took a lot of advice. There are things that you can do to help get visas processed. A lot of inside knowledge. Last year, for the Voices of the Revolution project, everybody got their visa because we dedicated more resources to the process. It’s really hard, particularly if the person is from a Trump-banned country. If they (an artist) are from the Middle East, it’s really difficult. Southern African countries too. So we try the hardest through whatever issues there are. And we have never not invited people for a project because we thought that they wouldn’t get their visa because that’s a political statement in itself. It’s really important to do this (invite international artists to the UK), and it is always difficult. But it is something that I feel passionate about, and it seems that with (Donald) Trump things are getting worse. But things come around. The thing is to keep trying to bring people and make that point when they get through.

In Place of War has been quite successful in attaining funding from a range of sources including the Arts Council England, the PRS for Music Foundation, the Anna Lindh Foundation, and the Mark Leonard Trust. This funding has been against a backdrop of an anti-refugee sentiment in Britain fueled by the Brexit vote. Has the rise in racist sentiment since led to an even more hostile environment to receive funding or has it made the need for such projects clearer?

We get funding from different places. We just put in a bunch of applications to work with refugees. I don’t know if has changed the landscape. Actually, we got funding from Europe to work with refugees. It’s obviously a clear priority. I think what Brexit did was highlight issues that people like me didn’t know were there. It was pretty much a 50/50 split in the UK around the idea of immigration (with the vote), and what that means for the country. Things have become quite fragmented again, and that’s really, really sad. I can’t see it (racism) because I live in Manchester which is a multicultural community. Right outside my door are people from all different countries on my doorstep. And I live it (in a multicultural environment). I’m from Brierfield (in Lancashire county) though. It’s one of the most racist towns in the UK. So I know what racism means. I moved away so I don’t see that. It is very rare that you see anybody be racist in Manchester.

I can’t have it. I couldn’t live in a place that had it.

I went to a wedding recently, and I was somewhere that is a white people’s place completely. That kind of freaks me out because all of the time I am going around the world to different places. I really like that. But, yes, things have changed in the UK. What’s happening is really sad, and it makes the work that we do with the people we work with, and the work that they do really important. It’s about changing perceptions and telling peoples’ stories. Nobody wants to leave their homes. This idea that refugees choose to come to the UK is a myth propagated by the right wing media, and it is so damaging to everything. If I can help, and work toward helping people have an alternative narrative to what the Daily Mail—which is the worst newspaper in the world…I don’t know if means that something is changed, but funding in the UK right now is not great. It’s not good.

With the uncertainty of the future of Brexit, you aren’t likely to get funding from the UK government.

Nobody knows what’s going on. In terms of solutions for our funding strategies, what we are thinking about quite often is looking outside the UK. Most of our work is outside the UK. What we decided to do was to start to prioritize working with the refugee community in the UK. I think that’s really important. I don’t know if one of the funding priorities has changed so much; especially with the government that we have, and all of the different things around Brexit; and also our relationship with Europe. It is a kind of in flux, and we don’t know how things are going to look in two or five years. So it’s about continuing doing the work that we do which I think is more important now than ever before.

Last year with Voices of Revolution, In Place of War brought together different voices from a collective of female musicians from 10 countries including Egypt, Brazil, and Venezuela. Part of your new funding is going toward the GRRRL global series this year.

Yes. We have been successful with quite a few more grants. We seem to be doing quite well at the moment convincing people that this is really important work. Bringing people together. Not purposely, but it just happened that all of the artists that we were bringing (to the UK) were male artists for the first three years of the Voices of the Revolution project. Through our networks internationally, we would ask people to suggest artists and, generally, it was always male (suggestions). We changed that last year. We insisted that it be all woman artists. It was the most powerful project that I have ever been involved in. Twenty-six women from a bunch of different countries, and contexts. The way that they came together, and built this family around music was so phenomenal. It was moving not only to me, but to everybody in my organization, and then to the UK audiences who literally followed them from show to show to show. They went to every single thing that the women did. In my past, I was a musician, and I remember the struggle that I had as a female musician in a female band in the late ‘90s.

[Fusing together techno, hip-hop, dancehall, reggae, soul, and electronica, GRRRL is a collaboration between woman artists from around the world coming together to tell their collective stories of life, conflict, inequality, and change through music.]

When I walked into the rehearsal room last year I burst into tears because there were 26 women from all around the world there making the most phenomenal music on their terms in a very different way than men make music. There was something incredibly powerful about that. Most of these women were women of color as well. So you are talking about people who are really the most marginalized in society who had come together. And, all of a sudden, we had this collective voice, and all of the music, regardless of the languages they were singing in, regardless of the sound of the music, it was about the struggles of women and it kind of manifested itself through these different songs. It was just phenomenal.

All of my work is about helping to give a voice to those people who just don’t get that type of opportunity. I have managed to push through in terms of being a woman based in Manchester who always wants to work with the grassroots, but kind of works in the music industry, and who has done something quite different. That has always been quite challenging to me, but I enjoy that.

Despite more women moving into education, politics, and into the work force in many of the locations you work, there’s still a significant gender inequity in many of those places.

Yeah, it has changed in the UK, but in the places that we work with it hasn’t. One of the African woman we work with, Awa, she is from the township in Makokoba, a poor suburb of Zimbabwe’s second city of Bulawayo. She’s the only woman making hip hop in her country (in the Zimbabwean language, Ndebele). What she is talking about through her hip hop is domestic violence. It’s about rape. Women in these countries generally don’t work. They don’t have these type of opportunities. They certainly do not get to make music. So they are talking (in their songs) about these different contexts, and the struggles of women. I think that there still is a huge struggle for women in the UK around equal pay, around rights, and all these kinds of things. But compared to Zimbabwe (a country where two-thirds of females report having experienced some form of gender-based violence) things are completely different here.

The Palestinian hip hop crew DAM has a powerful song “Who You Are” that speaks of oppression of women by way of lyrical dialogue between its male members, and musician/actress Maysa Daw. To hear such lyrics as “I am her life partner, but mostly I am a criminal” from a Palestinian group is quite striking.

Completely. Completely.

[ The video of “Who You Are” can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=DAM+%2B+Who+Am+]

Research must be of great importance to the success of In Place of War.

In Place of War started out with research, and it started out with a question, “Do people make art when bombs are dropping on their heads, and if they make art why? Why in a time of such crisis would you come to make art?” And then the question, “What kind of art would you make when bombs are dropping on your head? How does that change after the conflict ends, and people move away from the conflict?” This produced academic research. There were a whole bunch of books. One of them, “Performance in Place of War” (Seagull Books, 2008) looked specifically at performances in a bunch of settings.

In Place of War obviously evaluates the impact of its programs.

We do that ourselves. We are trained to understand the value of the art on team building, and on social transformation. So, if we are approaching a big donor, and we are talking to them about how we can facilitate change in a community, they will be like, “Okay, we are going to think about war, HIV and all of these things.” We come along, and say, “We want you to also think about the art.” In university, in terms of academic research, what we have seen internationally is that this is a huge vehicle for making really big change. So we are keen to measure that and demonstrate that so we can have solid data if we do these kinds of projects, or if we build a cultural space in the middle of the Congo in order to determine the impact it can have on those communities.

In Place of War works with creativity in territories of conflict through five primary strands of work: Research, education, production, networks, and digital. That is the core of the organization?

Yes. Basically, I would describe what we do is that we work with creativity. So, of course, with all art forms, and with music being one of the focus art forms. And we work with creativity, making change in communities, in the most marginalized communities in the world. These are communities that face violent conflict; and we work with people suffering the consequences of violent conflict like with refugee communities. We work with creativity as a tool to make change. And we work with a support system. We work with creative organizations from the ground in refugee camps; in all sorts of different settings. And these are usually young people Young change makers who have projects involving music or the arts, and we support those organizations increase the impact of what they do with the tools that you just talked about. The five strands of work. So we are essentially a support system for people in communities making huge change.

In speeches you have described how to make change when people have virtually nothing. And, in one of your blogs, there was an intriguing message about creating physical spaces to work. You spoke of visiting Caracas, Venezuela where, housed in recycled shipping containers situated between a military compound and a violent barrio, Tiuna El Fuerte provides a neutral space for the local community to experience a range of art practices from theatre to street dance.

As well, you have spoken about PAWA254, an alternative work space in Nairobi, Kenya which is home to photographers, graphic artists, journalists, musicians, filmmakers, writers, designers, and poets.

Much of the change happening in these regions can be attributed to people now being able to interact through the internet so these spaces can now resonate both locally and with other parts of the world.

I think it’s either of two things. First, this idea of physical space is really important. Where people can come together, especially people who have been left out of the normal system, have a space to come together. And I guess where creative (cultural programs) or the music is the magnet that brings people into that space, and amazing things can happen, and that’s really powerful. Where we have seen this is in places like Brazil, and Colombia. Colombia with hip hop schools in the barrios. Brazil with that space of AfroReggae Cultural Group in Rio de Janeiro. These spaces, once they are created, can completely transform a community. They help develop transferral skills in people. They help develop community. They help people come together and stay away from violent or negative activity. We see these spaces, especially in a country like Brazil, where these places were completely violent, and people couldn’t go there. Now, in a lot of these spaces, a thousand people from the community every day access the spaces and are making art which is phenomenal.

[The AfroReggae Cultural Group is one of the foremost pioneering non-governmental organizations in the world. Since its inception in 1992, it has become a social enterprise empire comprising over 75 projects and around 6,000 members in Rio de Janeiro that has expanded into other metropolitan areas in Brazil. With an increasing international presence, the AfroReggae Cultural Group has also worked on projects in Colombia, Canada, the U.S., the UK, China, and India.]

There is something about the physical (in developing creativity), but then the digital world is really interesting because there often is an opportunity for isolated people to connect and share. If you can imagine that you are in the middle of a war zone, and you feel like you are the only person that this is happening to, and you are struggling. How do you earn a living? How do you do the things that you want to do? Then (with the internet) you connect online. All of a sudden you can share your experiences with other people, but you can also see what other people in the same boat are doing. Then you can form networks of people who support each other. This can be really powerful.

So In Place of War brings people together from different contexts by using physical and digital models?

Yes, all of our work is about bringing people together. Often bringing people together from different contexts. So this year, as we discussed, we have the GRRRL project. Quite often we will take people from different contexts, and bring them together in the middle of the Congo or across to Brazil. Bring people together to experience different contexts, but also to share their expertise and ideas with people on the ground in those places. We do that physically, but now we have lots of Facebook groups and Whatsapp groups. People connecting with each other. It might be everyday people just saying “hi” on the group or they greet each other or, sometimes, they are sharing their work, or they are sharing their methodologies and ideas. But that’s really powerful because what was once very isolated community groups or individuals now have the ability to connect. Bringing people together has really positive benefits. I think quite often that we live in a world where people are constantly fragmented. People are told that they are different from other people, and people kind of separate themselves from each other. And that has a really negative impact on so many things in our society.

All of our work is. “How can we bring people together?” and the idea of “hagámoslo juntos,” which translated from Spanish means “Do it together” which I had tattooed on my back following an event we did in Colombia, bringing together people from different communities. It was incredibly powerful. The idea is that the most powerful things happen when people come together. I guess that underpins all of our work through creating spaces physically and digitally.

One of the aspects of the Arab Spring protests and demonstrations across the Middle East and North Africa that commenced in 2010 was the use of the internet. While visiting the Qalandia Refugee Camp in West Bank in November (2016) I was struck by one of the young teens there having a higher quality cell phone than the Westerners in our group. Surely, the connectivity we first saw with the Arab Spring is now shaping community interaction today.

I was in the Egyptian Revolution just after the first one (which demanded the overthrow of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak) writing a piece for The Guardian, just a few days before the second revolution. One of the things that came out from the artists that we interviewed was about this use of technology. What they said was that people were quite scared to talk about politics, but social media gave people anonymity so people could speak without too much chance of repercussion. As people started to talk more and more on social media, people saw that there were comments by others. Everybody had a comment about how they were feeling. Then that manifested social media to organize people. People going onto the streets and protesting. So Facebook and Twitter were the means of sharing contents about what was going on, and the means of galvanizing people onto the streets. Then the protests that were happening as the means to getting the message out to the world the reality of what was happening in Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo.

Digital connectivity has led to global communication evolving at an ever rapid pace.

Yes. Digital has been really important in our work. It’s about how you use it. There are digital tools that are available, and it’s what you do with those tools. The angle that I’ve always come from has been around thinking about music as culture and not commerce. So, for me, music is the most important thing. If you make money from it great, but it isn’t the most important thing about it.

As the late Factory Records, and In The City co-founder Tony Wilson famously said, “You either make money, or you make history.”

Well, that’s it. I think that is really important, that knowledge. And that changed through my life. At first, it was very much about that music culture, and then that changed very much to the social impact of music. That happened very organically, and that was from going to Medellin in Colombia and hanging out with a bunch of hip hop artists who said, “If it wasn’t for hip-hop, I would be dead. Hip hop gave me another option in life and I am truly thankful for that.” I thought, “Wow. Okay, what does that mean? What is the reality of that?” I thought of when I was much younger (as a musician) and now obviously going everywhere from Palestine to the Congo, I have found that music has this ability to change people. That’s what I am really interested in.

And I find that where you have music that changes peoples’ lives that is often the best music in the world because it’s music that comes from the streets. It is the music that has to be made. It is the music that is made often in times of difficulty or distress. It makes for incredible art that is meaningful. So that is what pulls me in, and makes me interested, and excited about music. The mainstream (of music) has never been that interesting to me. It has always been what happens on the margins that is interesting.

Digital now plays such a huge part in global and community interactions in driving social change.

We see that time and time again across the world where people are using their technologies to talk about their reality. In Brazil, we work with Media Ninja (a citizen journalism initiative based in Rio) one of the biggest alternative journalistic platforms in the world. These are a group of guys who basically just used their phones in a protest to stop police brutality. This has grown to be one of the most engaged with media platforms in Brazil. This is a group of young kids, 20 years olds, using mobile technology, and social media platforms to tell their reality, and to tell their story. That is where things get really interesting because if you think about millennials, and if we think about people younger than Millennials for the next generation, these are people who don’t engage with any form of traditional media. They aren’t reading newspapers. They aren’t reading magazines. They are engaging online through social media. So we actually have this more democratic system of people being able to tell their own stories, and social media then becomes really, really interesting. There are a lot of negatives to what happens on social media, but the fact that you can have a kid in a favela with a phone telling their reality, telling their story, that is powerful because, in the past, you would never hear that version of reality or that alternative narrative. So digital is so huge in what we are involved with.

You were raised in Brierfield, near Burnley. When did you come to Manchester?

I came back to Manchester. I was born in Manchester. I came back when I was 20. My sister Fiona came as well. The thing about Brierfield is that we lived in this place that nobody had ever heard of, but there’s this music community there which is a lot of people who have gone on and they have played with other well-known bands. Like one of the guys we know, Christian Madden, plays keyboards with Liam Gallagher now.

I recall that bassist Bernie Calvert of the Hollies came from Brierfield.

So exactly. There is a real hot spot of music there. We were really lucky ending up in this place where we became part of this little music scene. There’s a blues festival that takes place down the road in Coine. There were always gigs to go to. That was part of our teenage years, hanging out with loads of amazing players. Really good musicians that helped shape who we are.

Your sister Fiona is with the Manchester band the Whip.

My sister, yes she’s a drummer. She drums with the Whip, and on various projects, Including with Soulwax, Robyn and all sorts of bands. She’s a DJ as well. Fiona and I used to be in a band together called Earl. You know like Noel and Liam Gallagher? Honestly, I can‘t work with Fiona. After being in a band together for a long time, we parted ways, which is a really polite way of saying it.

Growing up, your father insisted that you two should question traditional thinking.

My dad is a sociologist, and my mother was an English literature teacher. They were both teachers. My dad, he made us think about everything in different ways, and I think that was really important growing up. He was so unconventional in such things as how we should embark on the world, my sister and I.

Your parents took you both to anti-nuclear marches as kids.

I was in the local newspaper when I was two-years-old being shown in a photo at an anti-nuclear march. We’d got to go to protests all of our lives. My dad wore a Palestinian flag on his jumper. “These people are alright. They want us to make change.” My parents would philosophize about such things. I think that kind of rubbed off on my sister and I. That has made us both very active in wanting to make political change even outside of work. I can’t really count it as my work. I still now and then go and protest against some of the industries in the world. It is so important for me in some way to try while here to make some change. Something small. Something positive. Keep pushing that agenda because there’s so much that pushes against it.

You didn’t go to university.

No, I didn’t. I was supposed to go. I got really good results. I got all As throughout grade school, and when I was supposed to go to university, I remember walking in to get my results with my dad. All of my teachers were there, and they all came over to congratulate me, saying, “Ruth, you are going to the university of your choice.” My dad looked at me as to say “No. You are not.” Then he said, “No. You are not.” He said, “Because I want you to be in a band.” He wanted me to be in a band. “You are going to be in a band. You can always go to university later in life, but you need to a band.” And being in a band took me on a journey that has taken me to where I am today; having traveled all over the world, doing really fascinating work, and doing some great stuff. Otherwise, I would have done something else. I’m so glad that my dad gave me the permission, I guess, not to go to university.

It is ironic then that a part of In Place of War is based at the University of Manchester.

From not going to university, I have subsequently developed programs for university and developed courses. I have taught at university. All of these things. It’s kind of crazy. Yeah, I never went, and I may never go. I’ve been involved with all of these things like research and things without any qualifications. Constantly working with professors at the university. I get emails, “Dear Professor Ruth Daniel.” It is just so crazy to me that could be something that people think.

It is going to sound quite cheesy but my university has been the work, and the learning that I do. I’m not the sort of person who can sit in a room and read and read read. I learn everything from just being out there. For example, when we were in the West Bank recently, there were the experiences of going to a refugee camp, and talking to people. That’s where I get all of my fire and all of my ideas and all of my knowledge from. It is coming from people who have really engaged with me.

You co-founded Fat Northerner Records in 2003 for niché bands and artists that were unable get support elsewhere. Among the great bands on the label were Bone-Box, Vortex, Grand Volume, and Coupe DeVille.

I was 22. I was in a female band from the age of 12, as I said, called Earl. We mostly performed our own tunes. Then I performed with a jazz group. and then I was in the Fall for a little while. I was always in a band or I was playing with other people in bands. We were just disillusioned. It wasn’t really this thing that we couldn’t get a record deal. We got bitter about the music industry. We became disillusioned with the industry with all of these very young, and very rich A&R guys. At the end of the night, everybody was going to try to sign this one band. It felt like the industry was lazy, and it felt like it was very fickle.

Being in Manchester as well, we had a much smaller music industry. I knew everybody in the music industry in Manchester. Obviously, I don’t know everybody in the music industry in London. I felt at that time that we needed something for Manchester music. A vehicle for which it could get it out there. That is kind of what we did.

At 22, I didn’t know what I was doing really. We made a label, and we got really lucky. At that time, the Arts Council in the UK was in a much better position than it is in now. They gave us a bunch of money which was more than I had ever seen to release music. To work with bands. To take them to South by Southwest, and to take them to CMJ. Do those kinds of things. It was a learning curve, and it happened at the time when it was become harder to break bands, and to sell music. But I was really pleased with what we did because we worked with some really cool bands. We organized some really great tours. We released some cool records. I felt really happy we had an opportunity to do that. There really wasn’t that platform in Manchester for the sort of music that we worked with.

Meanwhile, with the emergence of Napster and other illegal music sites, the music industry was in a state of shock, and denial.

There was this moment where it was just getting crazy. The music industry’s response to digital was not anything like what we were talking about in our circle of friends involved with that type of music. At MIDEM, the keynote speaker was giving his talk, and they had a clock there counting up the number of illegal downloads that were taking place during his talk. It wasn’t just me but there were a lot of people in Manchester saying, “This is great for us. We can distribute product now. We can connect. We can make collaborations happen across borders. We can do all of this interesting stuff with digital.” And the music industry was slow to understand it, and people were clinging on to this old system of how they priced digital downloads and all of this kind of thing. It just made a lot of things fail.

Such indie Brit label imprints as Humble Soul, Concrete Recordings, Chocolate Fire Guard and others committing to working together led to Fat Northerner organizing a music industry event aimed at the grassroots DIY independent sector called Un-Convention as a reaction to In The City refusing to consider discussing DIY or alternative distribution.

That’s it. We were talking all of the time: Artists, labels, festival organizers, and designers in the music scene, and with those in that scene around music. We were all saying that “This is a great time for music. This is exciting.” We went to the organizers of In The City in 2008, and we said that we’d like to do is curate a part of In The City that about the idea of doing things together, do it yourself. The guy running the event said, “We don’t use words like that. We aren’t interested much in this kind of thing. We don’t want to have that kind of conversation. This is not important.” And we thought, “Hang on a minute. You know what? We are going to prove (our thinking) by having that conversation, and we are going to fill a hall.” And we did. We booked a church, and we did the event the same weekend as Into The City. So we had talks, a merch shop, and we had 20 bands playing. And we did it with no money, and we made it free. We just borrowed and stole to make it happen. And it was awesome. I look back on that, and it is a moment in my life that I get quite emotional about because we never knew that it was going to work. We just knew that we had this hunch that we needed to have this conversation, and it was amazing. Everybody was there. Everybody from the music industry, and everybody said, “This feels like the birth of the new music industry.” And it was. Everybody in that room went on to do the things that we talked about. Interacting with digital. All of the festivals, certainly in the UK, and the independents, got into that space.

[When the late Tony Wilson and his partner, Yvette Livesey launched In The City in 1992 the objective was to found a British version of MIDEM in Cannes or Austin’s South By Southwest. It did a fine job of uncovering such new talent as Muse, Coldplay, the Darkness, Snow Patrol, and the Arctic Monkeys. Wilson, however, died in 2007, and the conference lost direction. “In The City died with Tony, but the symbol of it died with Tony, and the model itself was sadly dying as well,” Dave Pichilingi, CEO, Sound City told CelebrityAccess in 2016.

In The City ended in 2012, eclipsed by Sound City in Liverpool, and by the Great Escape in Brighton.

Yes, it ended a few years later. I think it was because everybody was still trying to cling on to the traditional ways of doing things. Of course, we were doing it (releasing music) so we knew what was important. So our event happened, and what was brilliant about it was that we did it. It was always going to be a one-off and then we had this email from a guy in Belfast who came to the event. This was the thing. People came to the event from really far away. So we had this message from this guy from Belfast, and we an Un-Convention happen there quite quickly. Then, on the way to another event, I got another email from a guy in Australia who said, “I’ve heard about this. It sounds great.”

Then we started to work with people around the world.

We took it to India four times. Brazil several times. To Colombia and Venezuela. That was a change for me because that took me on a personal journey of understanding that music—particularly coming from a UK perspective—when you go to India, and it’s “Okay, so there’s this explosion of metal music In Mumbai, an explosion of rock music. How is an industry going to be created because there wasn’t an industry for that yet?” Go to Colombia, and it’s all about hip hop as an alternative to drug cartels, and drug-related violence. Okay, that’s a different thing. Then, in Brazil, it’s about metal in São Paulo. To me it was like this journey of understanding what music means in so many contexts and, and I think the big thing is for me, how important music is in peoples’ lives. Whether it’s in the middle of the jungle in the Congo or a refugee camp in Palestine or whether it’s in a club in London, music is just so impactful.

Un-Convention was supposed to be a one-off, but there’s been 80 editions around the world.

Yeah, so we made all of these editions of Un-Convention. The whole thing is doing things in a different way. Un-Convention happened quite often without any funding. Without any money. That meant it could be true to itself. It was always about making it accessible so you would have really diverse audiences. In Medellin, Colombia we took it to the barrios. We took it to places where we were told no white people had come before or not for a very long time. We took a bunch of not just white people but a bunch of people from across the world into these places that were, perhaps, perceived as “no go” areas. We just did some of the most fantastic learning and exchanges of ideas. Really remarkable things.

You have been to the West Bank several times and you are working with the Palestinian House of Friendship, a nonprofit, non-governmental organization in Nablus that serves the needs of children, youth and families negatively affected by ongoing conflicts in the region.

That’s right. I was there for the first time last year in April. A year later, we went to the PMX (the Palestinian Music Expo). It has been an eye-opening experience. We had been planning to do a project there for a long time, and then we had the opportunity to go and work there. We took a small group out with us, and I was thinking about how could we make this work. I sat with Mohammed (Sawalha) from the Palestinian House of Friendship, and he said, “We want to make a radio station. We’ve got the funding, and we had everything ready to go. Then the Israeli authorities wouldn’t let us have the radio station.” I said, “We have a radio station. We’ve collected all of this equipment in the UK. A festival had given us their radio station. So we have a radio station. What else do you need?” He said, “We want to make music here. We want to document our history.” So I said, “We have all of this (recording) equipment that you can have, and you can create a studio.” That is really where the conversation started, and it’s been a non-stop event. We are now waiting for the final letter that allows us to send the equipment. I think that with PMX as well we will be gifting some equipment to the Palestinian rap collective Sa’aleek for their studio, and working with Jabid as well in the refugee camp in Shafut, in East Jerusalem as well. I think it. It is really interesting to be part of what’s happening there. We are also looking at funding applications for a big program in Gaza, working with creative entrepreneurship in Gaza to help people make businesses from their creative talent. Personally, I’m committed to anything Palestinian I guess

Where else have you gifted studio equipment?

The places that we are gifting equipment to is in the West Bank in Nablus, and to four places in Uganda. To a prison and a cultural space in Northern Uganda in a war torn area. To a Congolese refugee camp in the west of Uganda; and to the Mpenija island in the middle of Lake Victoria where there are single woman and girls. It’s an area of poverty. And to an indigenous hip hop collective in Kampala. Also, we are creating our biggest music studio in Soweto in South Africa in this beautiful family community space where there are all sorts of beautiful creativity comes out. In October, we are taking a delegation of 20 people to Zimbabwe, and Soweto–record producers and musicians–to do training. We are training a lot of work around the equipment there, and we are training helping people how to use the equipment. We are taking in so much equipment and teaching programs around activism and other things.

More recently In Place of War developed an impressive Creative Entrepreneurship program. How did that come about?

All of the work we do In Place of War, and with Un-Convention is working with exceptional creative talent. What we were finding coming from Colombia is that we were getting emails and message from the guys in Comuna Trece, “All right, we have done this project, how do we now make a business plan?” Asking for advice all of the time. The more places that we went to the more questions people were asking us. So we made a program. We decided to put all of these ideas together. We worked with 40 countries across the world, and we drew up examples of innovations and best practices in creative from the Congo or from Palestine or from wherever. A creative space in Palestine. A creative space in Zimbabwe and we created what is now about 800 resources. It’s a fully-structured program certified by the University of Manchester with really important people.

How does the program work?

We develop trainers in different parts of the world, give them all of these resources, and then they deliver a program in a refugee camp or in a township in an African country. This gives people a set of ideas, and shares knowledge in places that wouldn’t usually be able to access that knowledge. We just finished putting it (the information) all into this huge tool kit book. What we found was that it’s all good and well that we have these digital resources, but quite often the places that we are going to don’t have the internet. So with this big book, people can document their journeys. At the end of the process, they create their business, and they pitch it, and then we give people mentors. It ‘s about delivering education in ways that work for everybody. I’ve been to Uganda, and the education system there is so bad. It’s a colonial import that doesn’t let people think. Our program is about analytical thinking. It’s about critical thought. It’s about getting people to really center their thoughts around what’s out there in the community. and the world.

With all your traveling do you have time for a relationship? Are married or in a relationship?

No. I did have a partner, but he’s completely bonkers. At the moment, I am single. I don’t know. It is quite difficult, isn’t it? I’ve made it work in the past. I guess it’s very difficult.

You recently were honored at the Artist and Manager Awards in London on April 3rd (2017) with a Pioneer award recognizing your role as a trailblazer in the British music industry.

That was really weird. I got this award. I was humbled and honored to get it. Robbie Williams got the award before me. I remember sitting on the side of the stage, and he was sitting next to me. It was a surreal moment. I never thought that this kind of thing would happen to me in my life. That was really nice getting recognition from the music community. I guess when I was growing up that’s what I always wanted. From being a girl in a band to making it in the music industry. But to make it on my terms, that was the best thing. It was an amazing thing to make it through being unconventional which was really cool. I never thought that it would really happen.

Larry LeBlanc is widely recognized as one of the leading music industry journalists in the world. Before joining CelebrityAccess in 2008 as senior editor, he was the Canadian bureau chief of Billboard from 1991-2007 and Canadian editor of Record World from 1970-80. He was also a co-founder of the late Canadian music trade, The Record. He has been quoted on music industry issues in hundreds of publications including Time, Forbes, and the London Times. He is co-author of the book “Music From Far And Wide.”

Larry is the recipient of the 2013 Walt Grealis Special Achievement Award, recognizing individuals who have made an impact on the Canadian music industry.